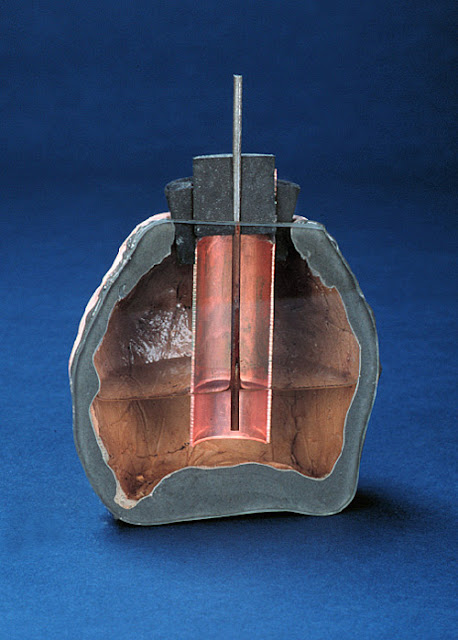

If you thought electric bulbs and batteries were modern European inventions, here is something to put that fact to question! A 1936 excavation of some 2000-years-old ruins in an ancient Baghdad village unearthed a small yellow clay vase about 6 inches in height. It had a copper-sheet cylinder lining within it that measured 5 x 1.5 inches.

A soldering material (most probably lead and tin) was used at the top edge of this mysterious cylinder, bearing remarkable affinity to modern solder alloy. A punched-in copper disk at the base of this cylinder was sealed with asphalt or bitumen. A similar asphalt layer also found at the top end held together an iron rod, bearing acidic corrosion marks inserted within the cylinder.

Ever since its recovery, several possibilities have been suggested by experts. Wilhelm König, the German archaeologist brought forth a startling idea that the clay pot could well be a form of electric battery. Following his theory, a Massachusetts based engineer Willard F.M. Gray created a model of this battery in 1940, filled it with copper sulfate solution and proved that it could produce electricity.

In 1970, the German Egyptologist Arne Eggebrecht followed in the footsteps of Gray. He supplanted the copper sulfate solution with fresh grape juice to generate about 0.87V of electricity for gold plating a silver statue. These experiments proved beyond doubt that 1,800 years old civilizations knew how to produce and utilize electricity by means of an acidic agent.

The path breaking conclusions of Konig lost its significance in the turmoil of the World War II. His European co-excavators had raised objection to his theories since the presence of batteries at a predominantly religious age seemed an unlikely possibility. However, soon a set of ‘ancient batteries’ were unearthed from the same sites in Iraq, inspiring a score of baffled propositions.

While some speculated that the electrochemical set up of the ‘batteries’ was meant to produce electricity, others refuted this claim. A series of thinly electroplated objects were found by König in Baghdad that probably used these cells though others opined that these were mainly fire-gilded. Demonstrative experiments have proved that though this battery uses a very primitive mechanism, it could plate a small object with a micrometer thick gold coat over two hours.

However, the electroplating theory was never unanimously accepted and other possible usages were suggested for these batteries. Paul Keyser hinted that the mild electric shock produced by using an iron bar in vinegar was used by healers or priests for electro-acupuncture. It could also have been a trick to create a sense of awe among devotees by electrifying the metal statue of a God.

Although these possible secular and religious applications for the ancient Baghdad batteries were credible, some archaeologists expressed their skepticism for the electrical theory. They raised questions on the absence of wires and the presence of bitumen insulators for the copper cylinder as the problem points of these so-called galvanic cells.

They pointed at the bitumen seal as an evidence for the clay pots being used for non-electronic, storage purpose. Accordingly, they said these were secure storage vessels for preserving sacred scrolls, parchments or papyrus documents within the airtight chamber of the cylinder.

However, in the Temple of Dendra in Egypt a stone relief seems to feature an electric lamp throwing light. The believers also pointed out that there was no soot in any of the pyramid shafts or underground tombs of Egypt, which must have stayed if the workers used fire as a source to make the elaborate carvings and decorations within the chambers. Many think, there must have been an alternate source of light other than fire and this speaks volumes in support of the battery theory. The concept of using polished copper plates for mirrors does not hold much ground as a promising source of light.

No comments:

Post a Comment